What’s the difference between an expiration date and a beyond-use date?

You pick up a prescription and see two dates on the bottle: one from the manufacturer, another from the pharmacy. One says expiration date, the other says beyond-use date. They look similar, but they’re not the same. Mixing them up can mean taking a drug that’s lost its strength-or worse, risking contamination. If you’ve ever thrown out a bottle of pills because you thought it was expired, only to find out the pharmacy gave you a shorter date, you’re not alone. This isn’t just paperwork-it’s about safety, money, and getting the right dose.

Expiration dates: what the manufacturer guarantees

An expiration date comes from the drug maker. It’s not a guess. It’s based on real lab tests. Manufacturers put pills, capsules, and liquids through years of stability testing under controlled heat, humidity, and light to see how long they stay effective. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) requires this for every approved drug sold in the U.S. Since 1979, this has been the law.

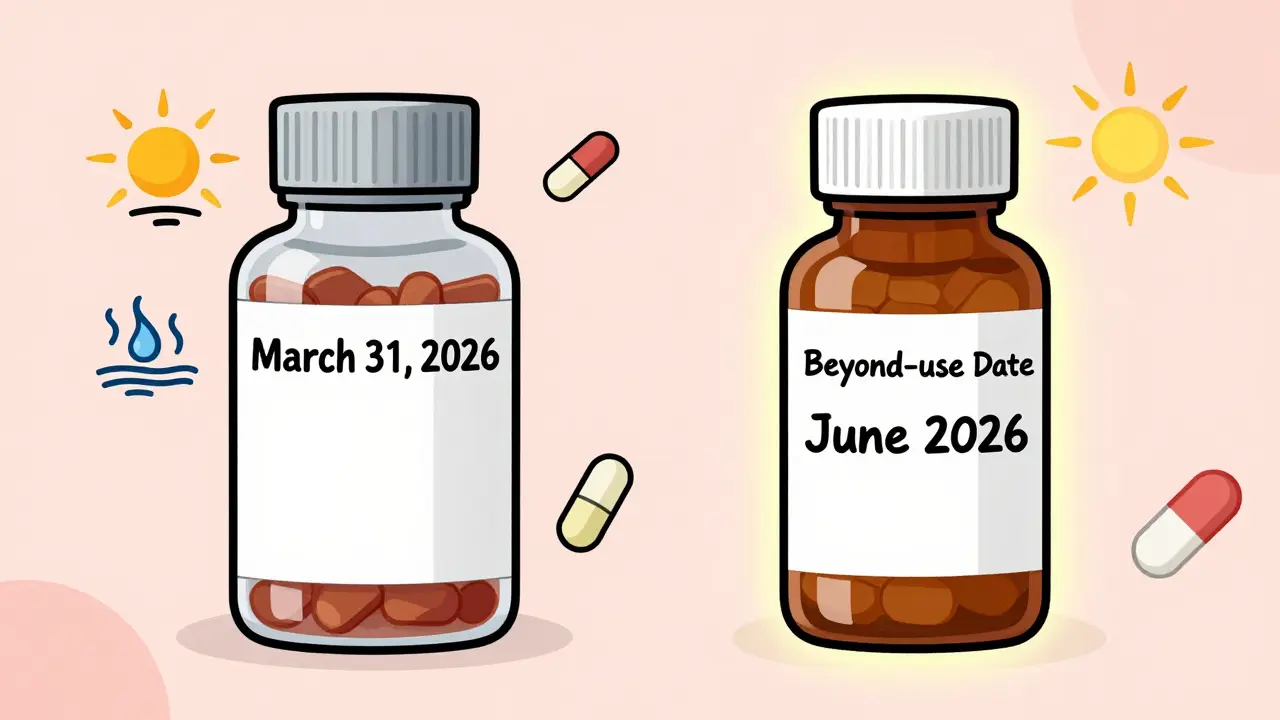

The expiration date is printed right on the original bottle or box. It’s a calendar date-like “March 31, 2026.” That means the manufacturer guarantees the drug will work as labeled up to that day, whether the bottle is open or sealed. If stored properly-cool, dry, out of sunlight-it should still be safe and potent.

Here’s the surprising part: the FDA tested over 100 drugs and found 90% were still effective 15 years past their expiration date, under ideal lab conditions. But that doesn’t mean you should take them. Real life isn’t a lab. Your bathroom cabinet gets hot. Your car gets cold. Humidity creeps in. The FDA says: stick to the date. They built in safety margins, but they can’t control how you store it.

Beyond-use dates: what the pharmacist sets

A beyond-use date (BUD) is different. It’s not from the drug company. It’s from the pharmacy. And it only applies when something changes about the medication. That could mean:

- Compounding a liquid version of a pill for a child who can’t swallow

- Repackaging bulk pills into daily blister packs

- Mixing two drugs into one solution for an IV

- Adding flavoring to make a bitter medicine palatable

These changes break the original manufacturer’s guarantee. Once you alter the formula, the shelf life changes. That’s where the pharmacist steps in. They follow standards from the United States Pharmacopeia (USP), which set rules based on how risky the compound is.

For example:

- A simple liquid made from two powders and water? BUD is 14 days if refrigerated.

- A cream mixed from approved ingredients? BUD might be 6 months at room temperature.

- A sterile injection? BUD could be 45 days if kept cold.

Here’s the catch: the BUD can’t be longer than the earliest expiration date of any ingredient used. If one powder expires in 6 months, the final product can’t last longer than that-even if the pharmacist thinks it’s fine.

Why the dates don’t match-and why it matters

Let’s say your doctor prescribes a thyroid pill that comes in 100mg tablets. The bottle says “expires 12/2027.” You get it from a big chain pharmacy. You take it for six months. Then you switch to a compounding pharmacy because you’re allergic to the dye in the brand-name version. They make you a custom liquid version. The new bottle says “beyond-use date: 6/2026.”

That’s not a mistake. That’s correct. The original expiration date no longer applies. The liquid formulation has no preservatives. It’s more likely to grow bacteria. It breaks down faster. Even if the original tablet would last until 2027, the liquid version must have a much shorter BUD.

Patients often get confused here. One survey found 68% of people on compounded meds threw out unused doses because the BUD ran out before they finished the prescription. That’s expensive. Compounded drugs cost 2 to 5 times more than regular ones. Wasting them hurts wallets and access.

Storage rules: what you need to know

Expiration dates assume “room temperature”-around 20-25°C (68-77°F), away from light and moisture. But compounded meds? They often need refrigeration-even if the original drug didn’t. Why? Because they lack stabilizers. A pill you could leave on your nightstand? The liquid version of it might need to live in your fridge.

Check the label. If it says “keep refrigerated,” do it. If it says “discard after 14 days,” don’t wait. A study by the International Academy of Compounding Pharmacists showed that improper storage cut the actual shelf life of compounded meds in half for many patients. That’s not a myth. That’s science.

And don’t assume “clear liquid = safe.” A cloudy or discolored solution? Smells off? Has particles? Toss it. Even if it’s before the BUD. That’s not a sign of age-it’s a sign of contamination.

What happens if you use a drug past its date?

Using a drug past its expiration or beyond-use date doesn’t always mean immediate danger. But it does mean risk.

For expiration dates: the main risk is reduced potency. Your blood pressure med might not lower your pressure as much. Your antibiotic might not kill all the bacteria. That can lead to treatment failure-or worse, antibiotic resistance.

For beyond-use dates: the risk is higher. Compounded meds can grow mold, bacteria, or fungi. If you’re immunocompromised, diabetic, or elderly, that’s dangerous. One case report from 2021 linked a compounded eye drop with a 3-month BUD to a patient’s corneal infection. The pharmacist had assigned a BUD that exceeded USP guidelines. The patient lost vision in one eye.

There’s no safety net. The FDA doesn’t test compounded meds. The pharmacy does. If they mess up the BUD, you’re the one who pays the price.

How to check both dates every time

When you get a prescription, always check for two dates:

- Look at the original manufacturer’s packaging (if you still have it). That’s the expiration date.

- Look at the pharmacy’s label. That’s the beyond-use date.

- Use the earlier date.

Example: Your pill bottle says “expires 10/2025.” The pharmacy repackaged it into a blister pack and put a BUD of “04/2026.” You use the 10/2025 date. Why? Because the original manufacturer’s date is the limit.

Another example: Your compounded liquid says “BUD: 05/2026,” but one ingredient in it expires in 11/2025. You use the 11/2025 date. The pharmacist should have done this. But you need to know to ask.

Ask your pharmacist: “Is this medication altered? If so, what’s the BUD and why?” Don’t be shy. It’s your health.

What to do with expired or outdated meds

Never flush them. Never throw them in the trash. That pollutes water and risks accidental ingestion by kids or pets.

Take them back to the pharmacy. Nearly all U.S. pharmacies now offer free take-back programs. The National Community Pharmacists Association says 92% do. Ask when you pick up your next script. Most have drop boxes in the lobby.

If your pharmacy doesn’t offer it, check with your local health department or police station. Many host drug take-back days, especially in April (National Prescription Drug Take Back Day).

What’s changing in 2026

USP is updating its guidelines for compounded medications. New rules coming this year will tighten BUD limits for high-risk preparations-like injectables and oral liquids with multiple ingredients. Some BUDs may be cut by up to 30% to improve safety.

Meanwhile, the FDA is cracking down on compounding pharmacies. In 2022, they issued 27 warning letters for improper dating. That’s up from 19 in 2021. More oversight is coming. But until then, you’re your own best advocate.

Bottom line: know your dates, protect your health

Expiration dates = manufacturer’s promise. Beyond-use dates = pharmacist’s safety limit. One is for untouched drugs. The other is for altered ones. Confusing them is easy. Living with the consequences isn’t.

Always check both dates. Store meds properly. Ask questions. Return old meds safely. Your body doesn’t care about paperwork. It only cares if the drug still works-and if it’s clean.

Can I use a medication after its expiration date if it looks fine?

The FDA advises against it. Even if the pill looks normal, potency can drop over time. For life-saving drugs like insulin, epinephrine, or heart medications, even a small loss of strength can be dangerous. Storage conditions at home aren’t controlled like in a lab. Don’t risk it.

Why does my compounded medication have a shorter date than the original pill?

Because the pharmacy changed it. Adding liquid, removing preservatives, or mixing ingredients alters how stable the drug is. The original expiration date only applies to the unaltered product. Once the pharmacy modifies it, they must assign a new, shorter beyond-use date based on USP guidelines to ensure safety.

Do I need to refrigerate all compounded medications?

Not all-but many do. If your compounded medication requires refrigeration, it’s because it lacks stabilizers found in commercial products. Water-based liquids, creams with sensitive ingredients, or those made from powders often need cold storage to prevent bacterial growth. Always follow the label. If it says “refrigerate,” keep it cold.

Can I ask my pharmacist to extend the beyond-use date?

No. Beyond-use dates are set by law under USP standards. Pharmacists can’t extend them just because you want to. If the BUD is too short, ask if there’s a commercial alternative, or if the pharmacy can compound it in smaller batches more frequently. Don’t pressure them to break safety rules.

Are expiration dates the same in the UK and the US?

Yes, the system is very similar. Both countries require manufacturers to prove stability before setting expiration dates. The UK follows EU and WHO guidelines, which align closely with U.S. FDA standards. Beyond-use dates for compounded meds also follow similar international pharmacopeia rules. If you’re in the UK, the same principles apply: trust the manufacturer’s date for unaltered drugs, and the pharmacy’s BUD for anything they changed.

Alexandra Enns

January 24, 2026 AT 13:35Marie-Pier D.

January 26, 2026 AT 02:55Sawyer Vitela

January 26, 2026 AT 09:32Izzy Hadala

January 28, 2026 AT 06:00Elizabeth Cannon

January 30, 2026 AT 01:27blackbelt security

January 31, 2026 AT 10:58Patrick Gornik

February 1, 2026 AT 10:36Karen Conlin

February 2, 2026 AT 04:35Sushrita Chakraborty

February 2, 2026 AT 10:49Heather McCubbin

February 2, 2026 AT 16:52Tiffany Wagner

February 3, 2026 AT 21:22venkatesh karumanchi

February 4, 2026 AT 23:12John McGuirk

February 6, 2026 AT 17:16