When a bone breaks, your body doesn’t just sit back and wait. It kicks off a complex repair process that can take weeks or months. But what if a medication could speed that up? For decades, doctors have looked at calcitonin as a possible helper in fracture healing. It’s not a new drug - it’s been around since the 1960s - but its role in broken bones isn’t as clear-cut as some might think.

What Is Calcitonin, Really?

Calcitonin is a hormone naturally made by the thyroid gland. Its main job is to lower blood calcium levels by telling bones to soak up extra calcium and telling the kidneys to flush out more of it. In the 1980s and 90s, pharmaceutical companies started making synthetic versions of calcitonin to treat osteoporosis - especially in postmenopausal women. It was thought to slow bone loss and reduce fracture risk.

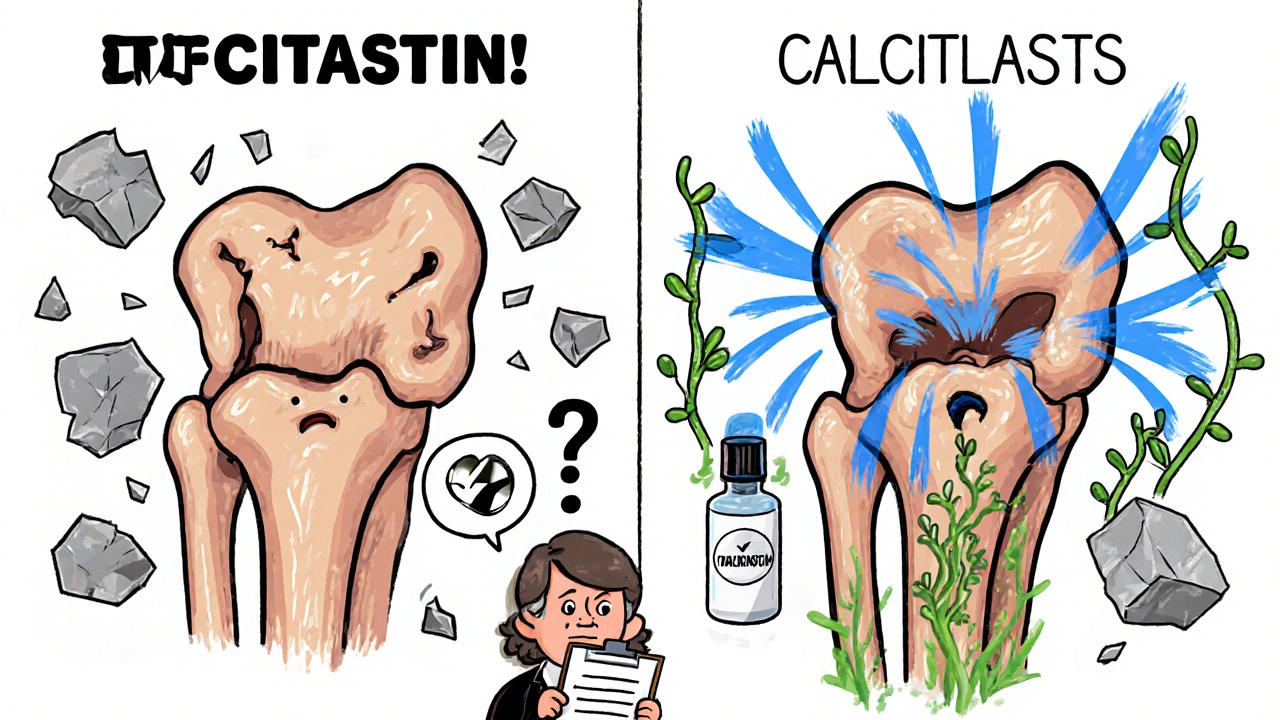

But here’s the twist: calcitonin doesn’t build new bone. It doesn’t act like teriparatide or romosozumab, which stimulate bone formation. Instead, it slows down bone breakdown by quieting down cells called osteoclasts. That’s why it was approved for osteoporosis. But when it comes to healing a fresh fracture, slowing bone loss might not be the same as speeding up repair.

How Fractures Heal - The Basic Process

Before we talk about calcitonin’s role, you need to understand how a broken bone mends itself. It’s not magic. It’s biology. Here’s the simplified version:

- Inflammation phase: Right after the break, blood rushes in. Immune cells clean up debris and signal the next steps.

- Soft callus formation: Within days, cartilage and fibrous tissue form a bridge across the break. This isn’t bone yet - it’s a temporary scaffold.

- Hard callus formation: Over the next few weeks, that soft tissue turns into woven bone. This is when real strength starts to return.

- Remodeling: Over months, the woven bone gets reshaped into strong, organized lamellar bone. This is the final stage.

Anything that speeds up any of these phases - especially the transition from soft to hard callus - could mean less time in a cast and less risk of complications. That’s where calcitonin comes in.

Does Calcitonin Actually Help Fractures Heal Faster?

Studies have been mixed. Some show a benefit. Others show nothing.

A 2014 study published in the Journal of Orthopaedic Research looked at 60 older adults with wrist fractures. Half got daily calcitonin nasal spray for 8 weeks. The other half got a placebo. The calcitonin group showed faster callus formation on X-rays and reported less pain by week 4. Bone density in the fractured area also improved slightly more in the treatment group.

But then there’s a 2020 meta-analysis in the British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology that reviewed 12 trials involving over 1,200 patients with hip, spine, or forearm fractures. The conclusion? No significant difference in healing time, functional recovery, or re-fracture rates between those who took calcitonin and those who didn’t.

So why the contradiction?

One big factor is timing. Calcitonin seems to help most when given early - within the first week after the fracture. After that, its effect fades. Another factor is age. Most positive results come from older adults with low bone density. In younger, healthy people, calcitonin doesn’t seem to do much at all.

Who Might Benefit Most?

Not everyone with a broken bone needs calcitonin. But there are specific cases where it might make sense:

- Postmenopausal women with osteoporosis who suffer a fracture

- Older men with low testosterone and low bone density

- Patients on long-term corticosteroids (which weaken bones)

- Those with delayed healing or non-unions (bones that refuse to knit together)

In these groups, calcitonin’s ability to reduce bone resorption might give the healing process a little extra room to work. It doesn’t rebuild bone, but it prevents the body from breaking down the fragile new bone that’s trying to form.

One real-world example: a 72-year-old woman with a vertebral compression fracture. She’s on prednisone for rheumatoid arthritis. Her fracture isn’t healing after 10 weeks. Her doctor adds calcitonin nasal spray. Within 6 weeks, follow-up scans show signs of new bone bridging the gap. It’s not a miracle - but it’s a nudge in the right direction.

How Is It Given? What Are the Side Effects?

Calcitonin is usually given as a nasal spray (200 IU once daily) or as an injection. The nasal spray is more common because it’s easier to use. But it’s not perfect. Many people get a runny nose, nosebleeds, or headaches. Some report nausea, especially with the injection.

Long-term use (over 6 months) is linked to a small increase in cancer risk - not enough to scare most people, but enough that the FDA added a warning. That’s why calcitonin isn’t used for long-term osteoporosis anymore. But for short-term fracture healing? Six to twelve weeks is usually safe.

Also, calcitonin doesn’t interact with most medications. But if you’re taking other bone drugs - like bisphosphonates - your doctor needs to know. Using them together doesn’t help much and might increase side effects.

Why Isn’t It Used More Often?

Even though calcitonin has been around for decades, it’s rarely the first choice today. Here’s why:

- Better options exist: Drugs like teriparatide (Forteo) and abaloparatide (Tymlos) actually build new bone. They’re more effective for healing, especially in severe cases.

- Cost and access: Calcitonin is cheaper than newer drugs, but insurance often won’t cover it for fracture healing - only for osteoporosis.

- Limited evidence: Most guidelines (like those from the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons) don’t recommend it as standard care.

So calcitonin sits in a gray zone. It’s not useless. But it’s not a go-to, either. It’s more of a backup plan - something a doctor might try if other options aren’t available or if the patient can’t tolerate stronger drugs.

What Does the Future Hold?

Research is still going on. Scientists are looking at calcitonin in combination with other treatments - like low-intensity pulsed ultrasound or platelet-rich plasma - to see if they work better together. Early animal studies show promise, but human trials are still small.

There’s also interest in newer forms: injectable calcitonin analogs with longer half-lives, or even gene therapies that trigger the body to make its own calcitonin locally at the fracture site. None of these are available yet, but they’re being explored.

For now, if you’re healing a fracture and you’re over 65 with osteoporosis, ask your doctor: Could calcitonin help me? It’s not a magic bullet, but in the right person, it might just be the small advantage you need to get back on your feet faster.

Can calcitonin help heal a broken bone faster?

Yes, in some cases - especially in older adults with osteoporosis. Studies show it can speed up early bone callus formation and reduce pain when used within the first week after a fracture. But it doesn’t work for everyone, and it’s not as effective as newer bone-building drugs like teriparatide.

Is calcitonin still used for osteoporosis?

It’s rarely used as a first-line treatment anymore. Newer drugs that build bone are more effective. Calcitonin is mostly reserved for patients who can’t tolerate other medications or for short-term use after a fracture. The FDA added a cancer risk warning for long-term use, which reduced its popularity.

How long does it take for calcitonin to work on a fracture?

Most benefits show up within 2 to 4 weeks, especially in pain reduction and early callus formation. For best results, treatment should start within the first week after the fracture. It’s not meant to be taken for months - 6 to 12 weeks is typical.

What are the side effects of calcitonin?

Common side effects include nasal irritation, runny nose, and nosebleeds (with the spray). Injections can cause nausea, flushing, or dizziness. Long-term use (over 6 months) has been linked to a small increased risk of certain cancers, which is why it’s not recommended for extended periods.

Can I take calcitonin with other bone medications?

It’s not usually recommended. Combining calcitonin with bisphosphonates or other anti-resorptive drugs doesn’t improve healing and may increase side effects. Always tell your doctor about all medications you’re taking before starting calcitonin.

Emily Barfield

November 2, 2025 AT 01:51So… we’re just supposed to believe that a hormone that literally tells bones to stop breaking down is magically going to make them grow faster? Where’s the mechanism? Where’s the proof it doesn’t just delay resorption while the body does the actual healing on its own? I’m not saying it doesn’t help-I’m saying we’re attributing magic to biology because we want a simple answer to a complex problem.

Sai Ahmed

November 2, 2025 AT 08:25They’ve been hiding the truth about calcitonin since the 90s. Big Pharma doesn’t want you to know it’s just a placebo with side effects. The FDA warning? That’s because they know it’s linked to tumors-but they’re still pushing it for ‘short-term use’ while they roll out the real cure: nanotech bone regenerators in secret labs. You think they’d let a cheap nasal spray compete with $10k biologics? Think again.

Albert Schueller

November 4, 2025 AT 05:22It's interesting to note that the 2014 study had a sample size of only 60 participants, which is statistically insignificant for a population as diverse as elderly fracture patients. Additionally, the 2020 meta-analysis, which included over 1200 patients, is far more robust. The fact that calcitonin is not recommended by AAOS speaks volumes. I'm not saying it's useless, but calling it a 'nudge' is misleading-it's more like a whisper in a hurricane.

Ted Carr

November 4, 2025 AT 15:42So we’ve got a drug that’s been obsolete for osteoporosis, now being resurrected as a fracture ‘helper’ because… what? Because someone had a runny nose and felt better? This is the medical equivalent of putting a band-aid on a broken leg and calling it innovation.

Rebecca Parkos

November 5, 2025 AT 04:28I broke my wrist at 68 and my doctor gave me calcitonin spray. I was skeptical too-but within three weeks, the pain dropped from a 7 to a 2. My X-rays showed callus forming faster than my sister’s, who got nothing. I don’t care what the meta-analyses say-I lived it. If you’re older, osteoporotic, and in pain, don’t let ‘evidence’ silence your body. Try it. What’s the worst that happens? You get a runny nose for two months?

Bradley Mulliner

November 6, 2025 AT 23:08Let’s be real. People take calcitonin because they’re scared of surgery or don’t want to take real drugs. It’s a comfort medication. The ‘nudge’ is psychological. The body heals itself regardless. The spray gives people a sense of control. That’s not medicine-that’s placebo with nasal irritation. And now we’re legitimizing it with case studies? This is how quackery becomes policy.

Rahul hossain

November 7, 2025 AT 04:16Let me tell you something about calcitonin-it’s the forgotten child of endocrinology, raised in the shadow of bisphosphonates and then abandoned like a stray dog. The nasal spray smells like regret and saline. But here’s the irony: while the world chases flashy bone-builders, calcitonin quietly sits in the corner, doing the dirty work of slowing the rot. It’s not glamorous, but it’s not useless. In the right patient-elderly, frail, on steroids-it’s the unsung hero of orthopedic triage. The system doesn’t reward humility. But biology does.

Reginald Maarten

November 7, 2025 AT 17:17Actually, the 2014 study didn’t control for baseline vitamin D levels, which are a major confounder in fracture healing. Additionally, the ‘faster callus formation’ was measured via X-ray, which has low sensitivity for early mineralization. The 2020 meta-analysis used CT scans and biomechanical testing-far more rigorous. Also, the FDA warning about cancer risk was based on a 2012 Danish cohort study with a hazard ratio of 1.32 (CI 1.04–1.67), not anecdotal. And no, calcitonin doesn’t ‘prevent breakdown of new bone’-it suppresses osteoclasts systemically, which may interfere with the remodeling phase. So yes, it might reduce pain by reducing inflammation, but calling it a ‘nudge’ is scientifically inaccurate. It’s a blunt instrument with a narrow window of potential utility-and even then, the evidence is marginal.