Hyponatremia Risk Assessment Tool

Symptom Checker

Answer the following questions to assess your risk of hyponatremia:

Risk Assessment Result

Click "Assess Risk Level" to see your risk assessment based on symptoms and medications.

When the heart can’t pump efficiently, the body’s fluid system goes into overdrive. One hidden side‑effect of that stress is a drop in blood sodium - a condition called Hyponatremia. Low sodium worsens swelling, fatigue, and even the risk of sudden death in patients already battling Heart Failure. This article unpacks why the two are linked, how doctors spot the problem, and which treatments actually work.

Key Takeaways

- Hyponatremia is the most common electrolyte disorder in heart‑failure patients and predicts worse outcomes.

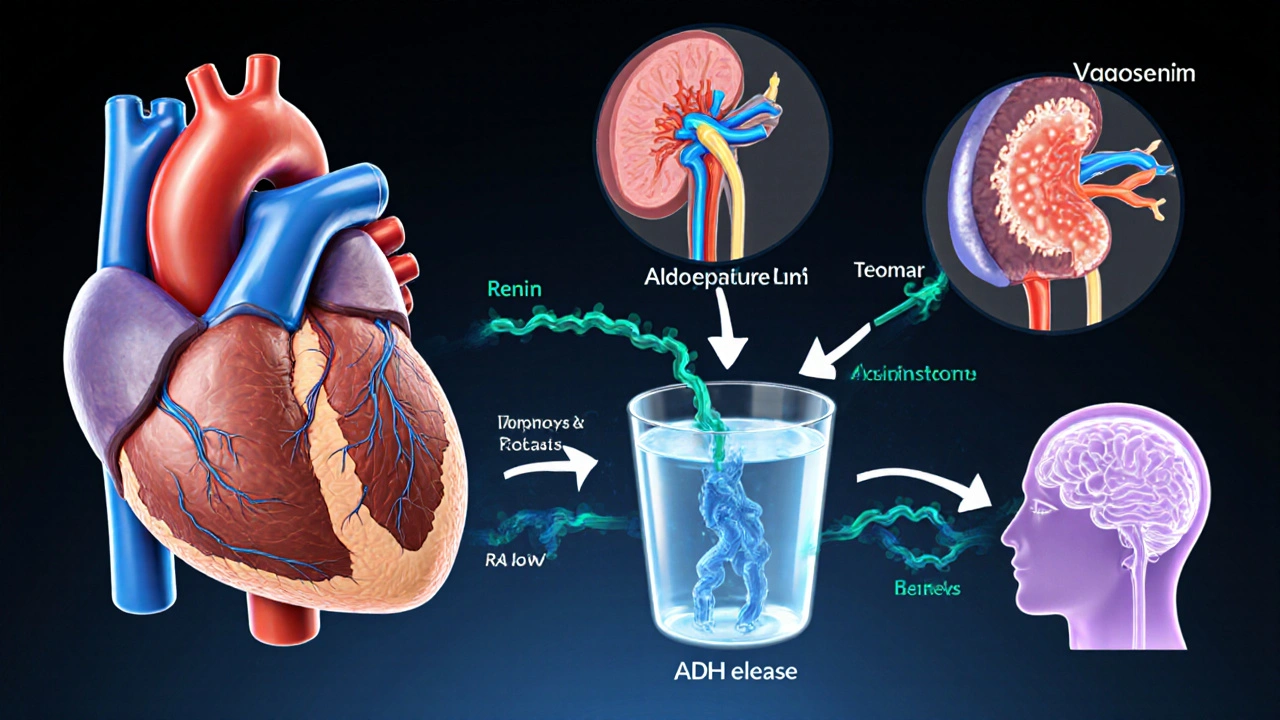

- Reduced cardiac output triggers hormonal pathways (RAAS, ADH) that force the kidneys to retain water, diluting sodium.

- Symptoms often mimic heart‑failure progression - watch for confusion, nausea, and rapid weight gain.

- Management blends gentle fluid restriction, judicious diuretic choice, and newer agents like vasopressin antagonists.

- Close monitoring of serum sodium and renal function cuts the risk of over‑correction, which can cause neurologic injury.

What Is Hyponatremia?

Hyponatremia occurs when serum sodium falls below 135mmol/L. Sodium is the main extracellular cation; it helps regulate water distribution, nerve impulse transmission, and blood pressure. In heart failure, the drop isn’t usually caused by a lack of dietary salt but by an excess of water that dilutes the sodium already present.

Typical triggers in heart‑failure patients include:

- High‑dose loop diuretics that cause “contraction alkalosis” and stimulate antidiuretic hormone (ADH) release.

- Impaired renal perfusion that activates the renin‑angiotensin‑aldosterone system (RAAS).

- Excessive fluid intake encouraged by thirst from reduced arterial pressure.

How Heart Failure Disturbs Sodium Balance

Heart failure reduces forward flow, leading to lower arterial pressure. The body interprets this as a volume‑depletion signal and flips on three major hormonal circuits:

- Renin‑Angiotensin‑Aldosterone System (RAAS) - Renin release triggers angiotensin II, which narrows blood vessels and prompts aldosterone to make the kidneys re‑absorb sodium and water.

- Sympathetic Nervous System (SNS) - Increases heart rate and vasoconstriction, further limiting renal blood flow.

- Arginine‑Vasopressin (AVP) or ADH - Directs the collecting ducts to retain water without sodium, diluting serum concentrations.

The net effect is “wet” hyponatremia: total body water rises while total body sodium stays roughly the same.

Medications commonly used in heart failure, such as ACE Inhibitors and Beta‑Blockers, can blunt beneficial neuro‑hormonal activation but also contribute to Na⁺ retention patterns that complicate fluid management.

Clinical Presentation and Diagnosis

Because hyponatremia mimics worsening heart failure, clinicians rely on labs and careful history. Typical red‑flag signs include:

- Rapid, unexplained weight gain of >2kg in 24hours.

- New or worsening confusion, headache, or seizures.

- Nausea, vomiting, and loss of appetite, especially when fluid restriction feels “too tight.”

Blood tests should be ordered whenever a patient with known heart failure reports these symptoms. A serum sodium < 135mmol/L confirms hyponatremia, while concurrent measurements of serum osmolality, urine sodium, and urine osmolality help differentiate “hypovolemic,” “euvolemic,” and “hypervolemic” patterns.

In most chronic heart‑failure cases, the scenario is hypervolemic hyponatremia: high urine sodium (≥20mmol/L) with elevated urine osmolality (>100mOsm/kg) despite fluid overload.

Managing Hyponatremia in Heart Failure

Effective treatment strikes a balance between removing excess fluid and avoiding a too‑rapid rise in sodium (which can cause osmotic demyelination). The usual algorithm looks like this:

- Assess severity. If sodium < 120mmol/L or neurologic symptoms are present, admit for close monitoring.

- Fluid restriction. Limit intake to 1.2-1.5L per day. This modest restriction is tolerable for most out‑patients.

- Adjust diuretics. Switch from high‑dose loop diuretics to a combination of loop plus thiazide‑type agents only when needed, because thiazides can worsen hyponatremia.

- Consider Tolvaptan, a vasopressin‑V2 receptor antagonist, for patients who do not respond to fluid restriction. Tolvaptan promotes free water excretion without significant sodium loss.

- Optimize heart‑failure meds. Ensure target doses of ACE inhibitors or ARBs, beta‑blockers, and mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists are reached, as they improve overall hemodynamics and reduce neuro‑hormonal drive.

- Monitor trends. Check serum sodium every 6‑12hours during acute correction; aim for a rise < 8mmol/L per 24hours.

In refractory cases, hypertonic saline (3% NaCl) can be given in a controlled ICU setting, but only when neurologic urgency outweighs the risk of over‑correction.

Common Pitfalls to Avoid

- Over‑aggressive diuresis. Too much loop diuretic can precipitate hypovolemia, stimulate ADH, and paradoxically worsen hyponatremia.

- Ignoring medication interactions. NSAIDs and certain antidepressants (SSRIs) amplify ADH effects.

- Failing to re‑measure. Sodium can bounce back after discharge; schedule a follow‑up lab within 1week.

- Excessive fluid restriction. Drastic limits (<800mL/day) lead to non‑adherence and dehydration.

Comparison of Hyponatremia Causes in Heart Failure vs. Other Conditions

| Feature | Heart‑Failure‑Related (Hypervolemic) | Syndrome of Inappropriate ADH (SIADH) | Hypovolemic (e.g., vomiting) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fluid Status | Volume overload, edema | Euvolemic, no edema | Volume depletion, low BP |

| Urine Sodium | >20mmol/L (often high) | >40mmol/L | <20mmol/L |

| Urine Osmolality | >100mOsm/kg, often >300 | >100mOsm/kg | >100mOsm/kg (concentrated) |

| Typical Triggers | Reduced cardiac output, high‑dose loop diuretics | Medications, pulmonary disease, CNS disorders | GI loss, diuretic overuse, burns |

| Management Focus | Fluid restriction + tailored diuretics | Drug‑induced ADH blockade, demeclocycline | Fluid replacement with isotonic saline |

Future Directions and Emerging Therapies

Research in 2024‑2025 highlights two promising avenues:

- Selective V2‑receptor antagonists. Newer molecules show a clearer safety profile than tolvaptan, with less liver‑enzyme monitoring.

- Remote hemodynamic monitoring. Implantable pulmonary artery pressure sensors give clinicians early alerts of rising filling pressures, allowing pre‑emptive diuretic titration before hyponatremia sets in.

These tools could reduce hospital readmissions and improve quality of life for the growing heart‑failure population.

Frequently Asked Questions

Why does low sodium matter in heart failure?

Low sodium signals that the body is retaining excess water, which worsens congestion, impairs breathing, and independently predicts higher mortality. Correcting it improves symptoms and may reduce hospital stays.

Can I drink water freely if I have heart failure?

No. Most guidelines recommend limiting daily fluid intake to 1.2-1.5L, especially if you have hyponatremia. Your cardiologist will tailor the exact limit based on weight trends and lab values.

Are diuretics the main culprit?

Loop diuretics are essential for relieving congestion, but high doses can trigger hormonal responses that dilute sodium. The trick is using the lowest effective dose and combining with agents that block ADH when needed.

What symptoms should prompt emergency care?

Sudden confusion, seizures, severe headache, or a rapid fall in sodium below 115mmol/L demand urgent treatment in a hospital setting.

Is it safe to use over‑the‑counter water pills?

Self‑medicating with OTC diuretics can cause dangerous swings in electrolytes, especially when you already have heart failure. Always discuss any new medication with your heart‑failure specialist.

Understanding the tight link between hyponatremia and heart failure lets patients and clinicians act before the condition spirals. By monitoring sodium, adjusting diuretics wisely, and staying alert to early warning signs, you can keep fluid overload in check and improve long‑term outcomes.

Andrew J. Zak

October 4, 2025 AT 13:11Fluid restriction is key but stay above 1 L to avoid dehydration

Dominique Watson

October 5, 2025 AT 03:05Hyponatraemia in the context of congestive heart failure constitutes a deleterious neuro‑hormonal feedback loop; it precipitates fluid retention and aggravates ventricular overload, thereby compromising cardiac output. The clinical imperative is to arrest this cascade through judicious diuretic modulation and vigilant serum sodium monitoring.

Mia Michaelsen

October 5, 2025 AT 16:58The pathophysiology hinges on excess ADH activity driven by low effective arterial volume, which in turn promotes water reabsorption and dilutes serum sodium. In practice, clinicians should first assess severity: sodium <120 mmol/L warrants inpatient observation, while milder reductions can be managed outpatient with fluid restriction of 1.2‑1.5 L/day and careful titration of loop diuretics. Remember to check concomitant medications such as SSRIs or NSAIDs that may potentiate ADH.

Kat Mudd

October 6, 2025 AT 04:05Let me break this down step by step because the nuances matter a lot in real‑world care. First, you have to recognize that hyponatremia isn’t just a lab number; it reflects underlying volume status and neuro‑hormonal drive. Second, the distinction between hypervolemic and euvolemic states guides therapy-if the patient is truly volume‑overloaded you’ll aim for a gentle negative balance rather than simply water restriction. Third, loop diuretics, while indispensable for decongestion, can paradoxically worsen hyponatremia by stimulating renin‑angiotensin‑aldosterone and ADH release, so the lowest effective dose is essential. Fourth, if fluid restriction alone fails, consider a vasopressin antagonist such as tolvaptan; it promotes free water clearance without significant sodium loss. Fifth, monitor serum sodium at least every 6‑12 hours during acute correction to avoid rapid shifts that risk osmotic demyelination. Sixth, remember that hypertonic saline (3% NaCl) is reserved for neurologic emergencies and must be delivered in a controlled ICU setting. Seventh, re‑measure electrolytes after discharge because rebound hyponatremia is common if diuretic doses are not appropriately adjusted. Eighth, always scrutinize the medication list-NSAIDs, certain antidepressants, and even some antidiabetics can blunt renal perfusion or enhance ADH activity. Ninth, patient education is critical; many patients underestimate how much “just a glass of water” adds up over a day. Tenth, consider remote hemodynamic monitoring if available; early pressure trends can prompt pre‑emptive diuretic changes before labs even turn abnormal. Eleventh, involve a multidisciplinary team-nurses, pharmacists, and dietitians all play a role in fluid management. Twelfth, document the target fluid limit clearly in the chart to avoid miscommunication. Thirteenth, be aware that low sodium itself is an independent predictor of mortality in heart failure, so correcting it improves not only symptoms but also long‑term outcomes. Fourteenth, in refractory cases, a trial of low‑dose demeclocycline can be considered, though monitoring for nephrotoxicity is mandatory. Finally, maintain a balanced approach: overly aggressive diuresis can precipitate hypovolemia and worsen renal function, while too lax a strategy allows ongoing congestion. All these steps together form a comprehensive, patient‑centred plan for managing hyponatremia in heart failure.

Pradeep kumar

October 6, 2025 AT 20:45From a physiological standpoint, the renin‑angiotensin‑aldosterone system intertwines with vasopressin pathways, creating a synergistic effect that amplifies water reabsorption-this is the crux of hypervolemic hyponatremia in decompensated heart failure. Leveraging natriuretic peptides or newer V2‑receptor antagonists can attenuate this loop, offering a mechanistic advantage over mere fluid restriction.

James Waltrip

October 7, 2025 AT 10:38Just so you know, the pharma giants don’t want you to discover the cheap alternatives that actually work; they push tolvaptan because it lines their pockets, ignoring the fact that an old‑school dietary sodium tweak combined with proper diuretic sequencing can neutralize the same pathway without a $1,200 monthly bill.

Chinwendu Managwu

October 7, 2025 AT 21:45Nice article but everyone knows the real cure is just stop drinking water 😂

Kevin Napier

October 8, 2025 AT 14:25Great summary-just a heads‑up: make sure the patient’s weight is logged daily; a 0.5 kg rise often signals fluid shift before labs catch up.

Sherine Mary

October 9, 2025 AT 04:18I’m constantly reminded how many doctors overlook the subtle neuro‑cognitive decline that even mild hyponatremia can trigger. You’ve got to be proactive with cognitive screening when sodium dips below 130 mmol/L, otherwise you’ll miss the early brain fog that patients often attribute to “just aging.”

Monika Kosa

October 9, 2025 AT 18:11Ever notice how every new guideline suddenly mentions “remote pulmonary artery sensors”? It’s all a data‑mining scheme to keep us hooked on proprietary tech while the old‑school echo still tells the whole story.

Gail Hooks

October 10, 2025 AT 05:18🤔 It’s fascinating how fluid balance reflects the broader equilibrium of life-too much restriction, and we feel suffocated; too little, we drown. Finding that sweet spot is both a medical and philosophical pursuit. 🌊

Derek Dodge

October 10, 2025 AT 21:58Just a note: the chart should list the target 1.2‑1.5 L fluid limit next to meds.

AARON KEYS

October 11, 2025 AT 11:51Correcting a typo: “hypertonic saline (3% NaCl) can be given” – it’s “hypertonic saline (3 % NaCl) can be given”. Small details matter in medical writing.

Summer Medina

October 12, 2025 AT 01:45The article skips over the fact that many patients are actually on over‑the‑counter NSAIDs which amplify ADH and make hyponatremia inevitable if you don’t flag it early the way a true clinician would always be on the lookout for hidden drug interactions especially when patients self‑medicate without informing their cardiologist it’s a glaring oversight that can turn a manageable case into a dangerous emergency the guidelines barely mention this but seasoned practitioners know it’s a common trap

Melissa Shore

October 12, 2025 AT 12:51In sum, the management algorithm hinges on three pillars: precise fluid restriction tailored to individual tolerability, strategic diuretic adjustment that balances decongestion with electrolyte stability, and vigilant monitoring of serum sodium trends to preempt rapid shifts. Incorporating vasopressin antagonists when standard measures fail provides a valuable adjunct, while emerging remote monitoring technologies promise earlier detection of volume overload. Ultimately, a multidisciplinary approach-integrating cardiology, nephrology, nursing, and pharmacy expertise-optimizes outcomes and reduces readmission rates for this high‑risk cohort.

Maureen Crandall

October 13, 2025 AT 02:45Well said